La storia di Martino Landi inizia 65 anni fa, a Lucca. Nato nel 1957 in una famiglia che ha avuto generazioni di esperienza nel settore delle arti e dell'artigianato, ha naturalmente mostrato segni di inclinazioni artistiche fin dalla tenera età. Dopo aver frequentato il Liceo Artistico, si diploma nel 1979 all'Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze con una Laurea in pittura. La famiglia di artigiani di Martino è la storia di quattro generazioni di scultori d'arte sacra; inizia a studiare il mestiere all'età di 16 anni lavorando a fianco del padre, la cui azienda Cromoplasto si specializza anche nella produzione di soldatini giocattolo. Il nonno e il bisnonno di Martino avevano consolidato la reputazione della famiglia producendo squisite figure di presepi religiosi, che tornarono ad essere l'obiettivo principale del lavoro dei Landi intorno agli anni '70, quando la domanda di mercato per i soldati giocattolo cominciò a diminuire. Il padre di Martino, Mariano Landi, produceva esclusivamente per l'azienda fiorentina Moranduzzo, che mantenne a lungo una posizione di leadership nel settore degli articoli natalizi in Italia. Nel 1994, a causa delle condizioni di salute di Mariano, venne stipulato un accordo con Moranduzzo, al quale i Landi affittarono la loro fabbrica e i loro macchinari, e che pagavano anche a Martino una percentuale dei ricavi, in cambio di nuovi articoli da produrre ogni anno. Questa partnership ha significato stabilità economica per l'attività dei Landi, ma purtroppo la produzione si è ridotta e nel 2003 Moranduzzo ha rilevato tutto e firmato un nuovo accordo con Martino - Per l'azienda è stato un affare sicuro in quanto le statuette del presepe Landi si erano affermate in tutto il mondo grazie alla maestria artigianale e artistica di Martino. Dal 2003 Martino non riceve più diritti d'autore e viene pagato solo per le statuette e il lavoro professionale svolto a Moranduzzo. Nel 2008, nel bel mezzo della crisi economica, Moranduzzo chiuse i battenti, non potendo sopportare e superare la concorrenza con produzioni a basso costo delocalizzate, come quella cinese. La seconda generazione della famiglia Moranduzzo ha poi riacquistato una parte della vecchia attività e ha cercato le competenze affinate di Martino, che ha continuato a svolgere il lavoro fino al 2018. Allo stesso tempo, ha continuato a insegnare pittura e disegno al Liceo Artistico di Lucca, lavoro che ha svolto dall'età di 27 anni. Negli ultimi anni, la domanda per le statuette magistralmente realizzate da Martino ha visto una drastica diminuzione: la globalizzazione ha reso poco redditizio per le aziende investire in prodotti artigianali, in quanto è diventato chiaro che è più conveniente fare affidamento su manodopera delocalizzata. In quasi 50 anni di esperienza, Martino ha sviluppato un sistema perfetto per la lavorazione di figure religiose. Il suo lavoro consisteva nel modellare statuette di cera dalle sembianze umane e animali, progettandole in modo che potessero essere duplicate attraverso stampi e prodotte in serie. La competenza unica di Martino risiede nel fatto di essere uno scultore, specializzato nella creazione di modelli di dimensioni molto ridotte, oltre ad essere in grado di realizzare vari tipi di stampi, sia metallici per la produzione di figure in plastica a basso costo, e gomma siliconica per la produzione di figure in resina. Inoltre, all'epoca curava l'aspetto colorante delle statuette; formulava specifiche combinazioni cromatiche adatte sia alla pittura manuale, sia alla colorazione meccanizzata delle figure religiose più economiche. Il settore lucchese, un tempo leader in questo settore, si trova ad affrontare tempi duri. Questo settore è stato colto impreparato dagli effetti della globalizzazione: al giorno d'oggi, i produttori stranieri tendono a copiare i prodotti originali, offrendo bassi costi di produzione, e il mercato delle figure religiose non ha fatto eccezione. La crisi Covid-19 ha ulteriormente aggravato la situazione di questo business già in difficoltà, poiché le aziende che producevano articoli pensati per i turisti non avevano più alcuna domanda di mercato per i loro prodotti. Questa battuta d'arresto ha comportato l'impossibilità, riporta Martino, di un ricambio generazionale che potrebbe mantenere vivo questo artigianato tradizionale. Non ha trovato, nelle generazioni più giovani, qualcuno a cui passare il mestiere: sembra che non ci sia nessuno disposto a ereditare la conoscenza e le tecniche che ha costruito e imparato nel giro di mezzo secolo. Se anche Martino, che ha una carriera di successo alle spalle, non può più trovare lavoro o profitto in questo settore, non ci sarebbe alcun motivo per dei giovani lavoratori per perseguire questo tipo di carriera. Il destino dell'artigianato di Martino sembra essere lo stesso dei professionisti con cui lavorava; ricorda con affetto un fonditore con cui ha lavorato prima che il mercato lo spingesse verso altri tipi di stampi. Ad oggi, il lavoro qualificato e specializzato del collaboratore di Martino non ha trovato apprendisti, quindi il lavoro di Martino, anche se fatto perfettamente, mancherebbe di uno step cruciale. Anche questo è una conseguenza degli elevati costi del lavoro in Italia, soprattutto rispetto ad altri sistemi produttivi a basso costo localizzati all'estero, principalmente in Asia. Nel mercato globalizzato di oggi e nel mondo digitale, Martino, che è un artigiano senior, manca delle capacità imprenditoriali e di marketing di cui avrebbe bisogno per prosperare. Internet ha dimostrato di essere una spada a doppio taglio: da un lato, avrebbe permesso ai Landi di evitare alcune decisioni imprenditoriali rivelatesi sbagliate e ha reso i loro prodotti conosciuti in ogni angolo del mondo. Dall’altro lato, Internet oggi significa che chiunque può guardare e copiare il lavoro di Martino; i clienti possono confrontare i prezzi e scegliere le opzioni più economiche, a scapito della qualità. Il lavoro di Martino non ha trovato molto beneficio nella digitalizzazione e modernizzazione; quando ancora realizzava figure religiose usava talvolta macchinari più moderni, ma il suo lavoro consisteva principalmente in prodotti artigianali tradizionali. Sa che le macchine 3D sono ormai molto popolari e utilizzate dagli artigiani in vari aspetti della loro produzione, ma non ha ancora trovato macchine 3D in grado di riprodurre la sua attenzione ai minimi dettagli e know-how artigianale. Egli afferma che le macchine 3D più sofisticate sono di solito quelle utilizzate da gioiellieri e ortodontisti, ma queste macchine raffinate in genere non possono adattarsi alle dimensioni delle sue statue. Ora in pensione dal suo lavoro di professore, Martino mantiene viva la sua passione. Continua a insegnare, privatamente, e a scolpire e dipingere, e si occupa anche di realizzare dipinti di animali su commissione – servizio che promuove anche attraverso la sua pagina Facebook e Instagram. Anche se appare evidente, come conclude Martino, che il mercato dei suoi piccoli capolavori artigianali ha attraversato tempi duri, e che il settore sembra essersi arreso, lui continua il suo lavoro nella sua casa di Lucca, spinto dall’amore e dalla passione per l’arte.

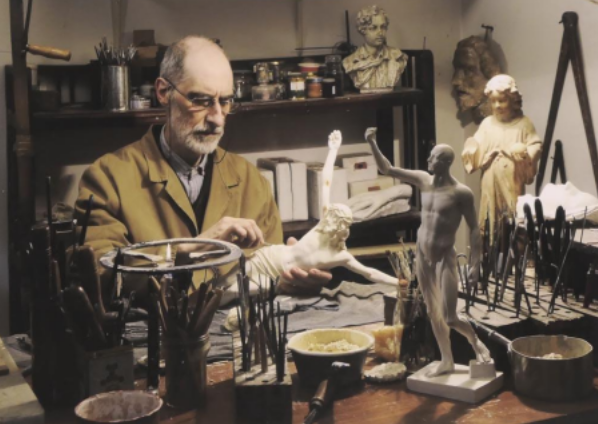

Martino Landi’s story begins 65 years ago, in Lucca. Born in 1957 in a family who had generations of experience in the arts and craftsmanship business, he naturally showed signs of artistic inclinations from an early age. After attending Liceo Artistico, he graduated in 1979 from Accademia di Belle Arti of Florence with a degree in painting. Martino’s family of artisans had a four generation history as sacred art sculptors; he started learning the trade at age 16 working alongside his father, whose company Cromoplasto also specialised in the production of toy soldiers. Martino’s grandfather and great-grandfather had made a name for the family by producing exquisite religious Nativity figures, which got back to being the main focus of the Landis’ work around the 1970s, when the market demand for toy soldiers began decreasing. Martino’s father Mariano Landi used to produce exclusively for Florence-based company Moranduzzo, which maintained a leading position in Italy’s Christmas items industry. In 1994, due to Mariano’s health conditions, a deal was made with Moranduzzo, to which the Landis rented out their factory as well as their machinery, and which also paid Martino a percentage of the revenues, in exchange for new items to be produced every year. This partnership meant economic stability for the Landis’ business, but sadly production tapered off and in 2003 Moranduzzo bought out everything and signed a new agreement with Martino - this was a sure deal for the company as Landi Nativity figures had become renowned all over the world thanks to Martino’s craftsmanship and artistry. After 2003, Martino no longer received royalties and was paid only for the statuettes and his professional work done at Moranduzzo. In 2008, in the midst of the economic crash, Moranduzzo shut down, as it was unable to endure and overcome its competition with delocalized low-cost productions, such as China’s. The second generation of the Moranduzzo family then bought back a portion of the old business and sought out Martino’s fine-honed skills, which he continued to ply until 2018. At the same time, he continued to teach painting and drawing at Lucca’s Liceo Artistico, as he had from the age of 27. In recent years, the demand for Martino’s masterful statuettes has seen a drastic decrease: globalisation has made it unprofitable for companies to invest in craftsmanship products, as it has become clear it is more cost-effective to rely on delocalized labour. In his almost 50 years of experience, Martino has developed a perfect system for the crafting of religious figures. His work consisted in modelling human and animal-figured wax statuettes, designing them so that they could be duplicated through moulds and produced serially. Martino’s unique expertise lies in the fact that he is a sculptor, specialised in creating very small size models, as well as being capable of making various types of moulds, both metal for the production of cheap plastic figures, and silicone rubber for the production of resin figures. Moreover, at the time he curated the colouring aspect of the statuettes; he formulated specific colour combinations which were fit for both manual painting, as well as for the mechanised colouring of the cheaper religious figures. The decline of an industry: globalisation and Covid-19 The Lucchese sector, once the market leader in this industry, is now facing tough times. This sector has been caught unprepared by the effects of globalisation: nowadays, foreign producers tend to copy original products while offering low production costs, and the religious figures field has been no exception. The Covid-19 crisis has further aggravated the situation of this already struggling business, as companies who produced tourist-designed items no longer had any market demand for their products. This setback has resulted in the impossibility, Martino reports, for a generational turnover which could keep this traditional craftsmanship alive. He has not found, in today’s younger generation, someone to pass the craft down to, and it seems there is no one to inherit the legacy of knowledge and the techniques he has built up and learned over the span of half a century. If even Martino, who has a successful career behind him, can no longer find work or profit in this sector, there would be no reason for young workers to pursue this kind of career. The fate of Martino’s craftsmanship seems to be the same as that of the professionals he used to work with; he recalls fondly a smelter who would make moulds for him, before the market made him move towards other kinds of moulds. As of today, the skilled and specialised job of Martino’s collaborator has found no apprentices, hence Martino’s work, if done perfectly, would be missing a crucial step. This, again, is a consequence of the high costs of labour in Italy, especially compared to other low-cost productive systems localised abroad, mainly Asia. Digital challenges for senior artisans In today’s globalised market and digital world, Martino, who’s a senior artisan, lacks the entrepreneurial and marketing skills he would need to thrive in his craftsmanship business. The Internet has proved to be a somewhat double-edged sword: on one hand, it would have permitted the Landis to avoid some poor entrepreneurial decisions as well as making their products known in every corner of the world. On the other hand, today’s Internet means that anyone can look at and copy Martino’s work; clients can compare prices and choose the cheapest options, to the detriment of quality. Martino’s work has not found much benefit in digitalization and modernization; when he still crafted religious figures he did sometimes use more modern machinery, but his work mainly consisted of traditional, handicrafts products. He knows that 3D machines are now widely popular and used by craftsmen in various aspects of their production, but he still hasn’t found 3D machines that can reproduce his attention to the tiniest details and handicraft know-how. He states that the most sophisticated 3D machines are usually the ones used by jewellers and orthodontists, but these refined machines generally can’t fit the size of his statues. Today Now retired from his job as Professor of Art, Martino keeps his passion alive. He continues to teach, privately, and to sculpt and paint, and also makes animal paintings on commission - a service he also promotes through his Facebook and Instagram page. Although it is evident, as Martino concludes, that the market for his small artisan masterpieces has gone through hard times, and that the sector seems to have given up, he continues his work from his home in Lucca, driven by love and passion for art.

New Educational Approaches for IT and Entrepreneurial Literacy of Senior Artisans

PROJECT:

2020-1-RO01-KA204-080350

New Educational Approaches for IT and Entrepreneurial Literacy of Senior Artisans

PROJECT:

2020-1-RO01-KA204-080350

The European Commission's support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.